Nikola Tesla’s Night of Terror – Review

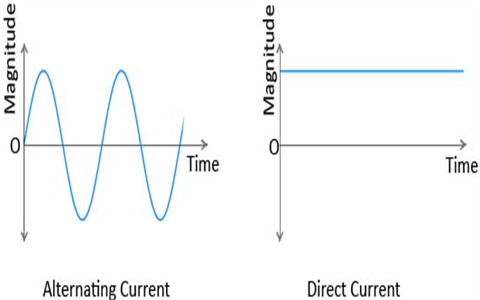

From its earliest beginnings, Doctor Who has always featured historical celebrity figures. From Wyatt Earp (in 1966’s The Gunfighters) to Charles Dickens (in 2005’s The Unquiet Dead), the Doctor likes to name drop, or drop in on names, from time to time. Nikola Tesla’s Night of Terror (a story which takes place longer than a single night but “Nikola Tesla’s Day and a bit of Terror” sounds less punchy) is novel because it features not one but two powerhouses; the titular character and Thomas Edison. Two scientists who, at the start of the twentieth century, were poles apart fighting their “war of currents” over electrical distribution (Tesla developed AC whilst Edison preferred his system of DC). Amidst this wind of change looms a more literal conflict, from a race of alien scorpions (yes, really) who want to get their grubby little pedipalps on Tesla’s skills. Contact has been made, resistance is futile…

The story begins, once again without a cold opening, with Nikola Tesla (Goran Visnjic) at his Nigara Falls generator plant. He’s demonstrating his work with his assistant, Dorothy Skerritt (Haley McGee), to potential investors. After the death of one of his employees, Tesla discovers that parts have been stolen from his machinery, making them much more dangerous. Investigating strange noises in his laboratory, he discovers a floating orb with luminous green markings on it. Startled by a mysterious cloaked figure, Tesla and Dorothy flee, meeting the Doctor as she bursts in through the door. They all escape on a night train to New York, where they meet up with Ryan (Tosin Cole), Graham (Bradley Walsh) and Yaz (Mandip Gill). The mysterious figure from Niagara Falls suddenly reappears, shooting at them with a Silurian blaster. The gang switch carriages and the Doctor loses him by uncoupling the rear cars. The hooded figure projects lightening from his hands as the ‘fam’ escape into the night (begging the question why he needed the blaster in the first place).

Tesla takes them to his laboratory in New York where protestors are demonstrating outside against what they believe is his “Death Ray”. Once inside he shows the Doctor the globe, which she identifies as an “Orb of Thassa”, a device designed to transmit information by its creators. This orb has been repurposed though… but by whom, and what for? Spotting one of Edison’s spies at the window the Doctor decides to pay him a visit. Meanwhile the figure from the train returns and attacks Edison’s lab, electrocuting everybody before chasing after the gang. The Doctor briefly traps the creature in a circle of chemicals before it teleports away to safety.

Back at the lab, more creatures appear and kidnap Tesla and Yaz, transporting them to their invisible alien ship high above the city. On board their leader, a hideous Racnoss scorpion-like creature forces Tesla to repair her ship (which in fairness seems to be working pretty fine). He refuses and, blowing a fuse, the queen threatens to hurt Yaz if he doesn’t agree. The Doctor teleports to the ship just in time, where she learns the alien is actually the Queen of the Skithra whilst the ship is Venusian by design. It’s a ship made of stolen parts that are breaking down hence their need for a scientist to repair things. Tesla is suitable because he identified the Martian message and replied. Stalling for time the Doctor startles the Queen and teleports Tesla and Yaz back to the Wardenclyffe lab. The Queen warns them to hand him over or she’ll destroy the Earth.

In the lab, the Doctor studies Tesla’s plans for his tower at Wardenclyffe, which was designed to wirelessly distribute energy across the planet. “That’s wi-fi”, says Ryan (no Ryan, it really, really isn’t). After an A-team style montage, they connect the TARDIS up to the tower as a power supply, prepping it to transmit a single bolt of lightning to destroy the Skithrah ship. As the Doctor raises an energy shield (in a move presumably stolen from the Master in Spyfall – how’s that for creativity?), the rampaging scorpions attack through the city; bad boys running wild. Barricading themselves in the lab, and apropos of nothing, the Doctor reveals the Skithra are in fact a hive mind; their strategy is simple – neutralise the Queen and win the game. Appearing in the lab, the Queen is tricked by the Doctor into using her teleport bracelet to return to the ship, just as the tower zaps it with electricity. Damaged, the Skithra ship escapes (or is it destroyed – it’s not clear).

After saying their goodbyes, the TARDIS ‘fam’ lament their inability to change events. The sting in the tail is that for all their efforts, Tesla will still die penniless and history (along with Ryan and Graham) will forget him.

The ‘war of currents’ between Tesla and Edison is like a simile for the different approaches to story-telling of Steven Moffat and Chris Chibnall. A Moffat story is very much like Tesla’s AC current, with its energy bursting backwards and forwards in exciting ways. His approach to stories carries the greater risk for failure, but it yields the more powerful results and travels further. Chibnall’s stories in contrast are like Edison’s DC currents – steady flows of simple ideas in a single direction. The chances for failure are greatly reduced, but its potency is also greatly diminished.

To draw a direct comparison between the two eras, let’s compare this week’s story to a celebrity historical from the Steven Moffat years, The Girl in the Fireplace (which I know might sound a little unfair, as this story has won a Hugo Award, but its my game and I invent the rules – okay?). As strange as it sounds, the two adventures share a great deal in common, albeit with the two narratives behaving in their respective AC/DC current states. Both stories are by their definition historicals but instead of beginning his in pre-revolutionary France, Moffat sets his stage in the future on a spaceship before rebounding it to the past, and back again, like the electrons in an AC current. Chibnall’s tale however is conventionally linear, conforming to his steadier DC model (it starts in the past and events follow chronologically). Both stories also hinge on the antagonists seeking the brain of their titular characters. In the Girl in the Fireplace, the clockwork robots literally require Reinette’s brain whereas in Nikola Tesla’s Night of Terror the scorpions require the scientist’s grey matter in a less literal, less surprising sense. Both enemies’s plans are stupid by design, but at least with the clockwork robots this effect is intentional. The audience only realises their mistake as events unfold; understanding that ultimately eludes the Doctor himself. The Skithra plan in Nikola Tesla’s Night of Terror is equally nonsensical but its presented to the audience as if it makes total sense. Their ship is ‘broken’ and needs fixing, despite its ability to fly, teleport people and turn itself invisible at will. With such an embarrassment of riches why do they really need an Edwardian scientist exactly? And what are Tesla’s qualifications to be the Skithra equivalent of Chief O’Brien? Because he intercepted a message from Mars? Laurence Scarman in the Pyramids of Mars (a story set a mere 8 years after this) also intercepts a similar message – would he be suitable? Actually, forget that – the idea of Michael Sheard travelling through the universe with a bunch of space scorpions is too wonderful to ridicule.

Another noticeable difference between Moffat’s and Chibnall’s stories is the impact they make on their characters. “Was that more or less impossible than your usual day”, Dorothy asks Ryan and Graham at the end of Nikola Tesla’s Night of Terror, only for them to shrug it off with a knowing look that suggested nothing of consequence had really happened. They were right though… there were no consequences to any of it and without consequences there can be no drama. In stark contrast, by the close of The Girl in the Fireplace the main characters are all profoundly altered. Mickey has proved himself to be a capable companion (to his friends but more importantly to himself) and Rose has felt not just the fear of her heart being used as replacement parts but also of being replaced in the Doctor’s hearts. As for the Doctor himself, he is perhaps never quite the same again in this incarnation after the stresses of this episode, such is the emotional wringer he’s put through. In the space of a mere 45 minutes alone he is:

However, in Nikola Tesla’s Night of Terror, the Doctor is mainly:

This isn’t Jodie’s Whittaker’s fault, one hastens to add. She is doing all that’s being asked of her. The problem is, that’s not a fat lot. The Doctor is very flatly written in this episode, the narrative hardly ruffling a hair on her head (it makes you nostalgic for the days when you knew Voyager’s Janeway was in trouble when she’d power walk around the ship with ‘bed-hair’). The scripts simply aren’t challenging her enough. If we analyze the eras of every modern Doctor, by this point in their respective reigns they’ve experienced deeply personal stories. By now, Eccleston had experienced a nervous breakdown in Dalek, Tennant had romanced Reinette in The Girl in the Fireplace, Smith had met The Doctor’s Wife and Capaldi had buried childhood trauma in Listen. The writers need to better serve the 13th Doctor. Allow her to feel something and we might just feel something for her in return.

While last week’s ironic message was about the dangers of carbon emissions, from an episode which only increased its ‘footprint’ by filming overseas, this week’s ironic message is that inventiveness is life’s most important aspiration, delivered by an uninventive script with a pound shop knock-off monster. The Skithra Queen’s costume has clearly been repurposed from the Racnoss in 2006’s The Runaway Bride, like some kind of Kirsty Allsopp shabby chic project. At least the Racnoss was anatomically consistent with its species. The Skithra Queen, despite belonging to a race of intergalactic scorpions, is curiously bipedal herself. It’s almost as if Sarah Parish waltzed off with the Racnoss’s legs after filming wrapped on the Runaway Bride, and they couldn’t afford new ones. The Skithra Queen is by far the worst aspect of an otherwise fairly polished production. Then again the BBC has a very good library of period props and costumes; less so a wardrobe of Pandinus Imperator.

Whilst on the subject of irony, It’s funny this episode also seeks to glorify the father of modern electricity (whilst at the same time overlooking his many flaws – dubious attitudes to women and a proponent of eugenics to name but a couple) through a medium invented by his arch-rival Edison; the moving picture. Maybe the Judoon police irony too, and thats the reason for their reappearance next week.

The Doctor is very flexible in her morality in this episode. She admonishes both Edison and Ryan for trying to defend themselves with guns against the Skithra but ultimately defeats the Queen by turning Tesla’s tower into a giant death ray (the very thing the protestors at the start are afraid of. Is the episode vindicating their bigotry or having fun with it? It’s unclear). In fairness, there’s a modern tradition of this type of resolution in Nu Who. Recent producers have clearly studied 1977’s The Horror of Fang Rock and copied its elegant solution (where the Doctor repurposes the story’s lighthouse as a laser to destroy the Ruton ship). 2006’s Tooth and Claw concludes in a similar manner with the Doctor using the giant telescope as a weapon, whereas in The Idiot’s lantern (also 2006) he weaponises the transmission signal from the broadcast tower. The ending to Nikola Tesla’s Night of Terror follows the same pattern; another idea straight from Edison’s sweat shop rather than Tesla’s fertile imagination.

The use of the TARDIS so far this series has been a very flexible thing too, however, in this episode it’s just downright strange. After the scene in the lab (at the beginning), the Doctor jokes to Tesla she’s “someone with a fast way out of here”, with the audience naturally assuming she means the TARDIS whereas in fact she means a night train to New York. So, where is the TARDIS in all this? Explanation A is it’s on the train, but if it is then it had better be in the front cars because the rear ones get detached in order to escape the disguised Skithra. More likely is explanation B which is it’s in New York, but that begs the question why they didn’t use it to travel to Nigara Falls in the first place. It certainly wasn’t for the delights of experiencing Edwardian locomotion because the ‘fam’ were sitting in an empty car at a makeshift table when the Doctor arrives, as if they’d smuggled themselves aboard. It’s not obviously nearby if it is in New York either; in fact it doesn’t appear until 25 minutes into the episode (I counted) and even then it casually appears as if it had been there all along.

It doesn’t even feature later in the episode, when the Doctor becomes stressed because Yaz and Tesla are being held captive on the alien ship. There’s no narrative reason why she can’t use the TARDIS to get there (she mumbles some unspecified rubbish about not being able to take it) but the scenes are played as if there is. It’s strange when you consider that Spyfall in contrast uses the TARDIS to freely solve its narrative problems. Oddly though at the end of the episode, the TARDIS is used, but only as a generator, even though Tesla clearly has parts for a functioning one of his own. So, the rule that’s established this series seems to be the TARDIS can be used for anything except stuff that its designed for – transportation.

On the subject of Spyfall, another of its new rules are broken here too. At the close of that story the Doctor erases herself from the minds of the historical characters she meets, like a member of the Men in Black (“Women in Black. Always get that wrong.” Copyright Chris Chibnall). At the end of this story, one where Edison is established as an unreliable parasite who steals ideas from others, the Doctor doesn’t have the foresight to wipe his mind. Maybe that light bulb will flash for her later?

VERDICT

A forgettable, DC current affairs story that preaches about ingenuity without contributing any new ideas of its own.

Positives:

+ Slightly (very slightly) more assertive Doctor early doors

+ Goran Visnjic is electrifying as Tesla

Negatives:

– Toothless story

– Too many companions

– Aliens that can shoot electricity out of their fingertips but need the help of a man who builds electricity generators.

– Embarrassing make-up design for Skithra Queen

– Dodgy CGI for scorpions

Power rating C+